INTRODUCTION

Marine Turtles are a successful group of animals that have witnessed the rise and fall of the dinosaurs. They have inhabited the earth for over 100 million years and survived in great numbers until recent past. They have evolved from large, land living tortoise-like animals. Their body consists of a head, short neck, pair of long fore flippers, pair of short and rounded hind flippers and a tail. Upper carapace and lower plastron make a protective structure (box) for internal organs. Unlike tortoises and freshwater terrapins they are unable to withdraw their head and limbs into their. Marine turtles do not have teeth but their sharp, beak-like jaws can crush, tear or bite depending on their diet, which varies according to species.

Turtles are reptiles (Class: Reptilia, Order: Chelonia) hence cold-blooded animals. Therefore, the environment determines their body temperature. In the morning, marine turtles ‘’sunbathe’’ at the surface of the sea to increase their body temperature. In the morning, marine turtles ‘’ sunbathe’’ at the surface of the sea to increase their body temperature. They have lungs to breathe air. Turtles rise to the surface to breathe every – 30 minutes. Over millions of years they have become very well adapted to living in a marine environment. With their long and muscular oar-like fore flippers, rudder-like hind flippers and their flattened, streamlined shells, marine turtles are fast and agile swimmers.

The only time marine turtles leave the ocean is when the females come ashore to nest. In some areas they can be seen having their ‘’sunbathe’’ on beaches or rocks. The males spend all their time at sea and little is known about their habits. Most species are highly migratory, moving between nesting and feeding grounds, which can be thousands of kilometres apart. We do not know exactly how long turtles live, but they are generally assumed to have a life span greater than 80 years. Time taken for sexual maturity depends on species. Olive Ridley Turtle, the smallest, takes 7 to 15 years, while herbivorous Green Turtle might take 50 years !. The remaining 3 species including the largest Leatherback Turtle takes 20 to 30 years. Until maturity it is difficult to distinguish between male and female turtles, when they reach maturity. Male turtles develop a long claw on each fore flipper and long tail. The way that an egg-burdened female finds her way to her nesting beach is still a mystery Some scientists believe that marine turtles are sensitive to earth’s magnetic field and use it for navigation. They are often found using not only the same sandy beach but also the very same stretch of beach they used in previous years .Hybrids and Albino specimens could be seen among the marine turtle species Today seven species of these ocean dwelling reptiles representing two families, Cheloniidae and Dermochelyidea remain. All of them are now threatened with extinction dueto man’s destructive activities.

MARINE TURTLE MATING & NESTING BEHAVIOUR

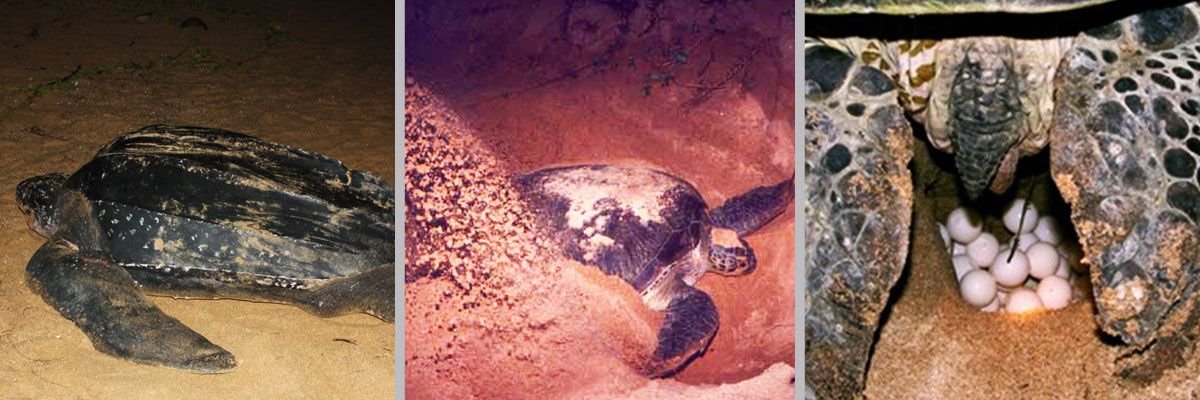

Turtles mate mostly during the daytime and it takes place in the shallow offshore waters. Some turtles mate submerged and others on water surface. Adult male turtles have well developed claws to hold the female firmly while mating. A single female can mate with several males during the mating season and store the sperms in her body. Eggs are fertilized with these stored sperms and therefore a single clutch may contain eggs fertilized with several males. When a female has located the nesting beach she waits in waters close to the shore until nighttime. Female turtles nest at night because it is cooler and in the darkness they are less conspicuous to large predators. Even after dark, the female turtle constantly surveys the beach for danger whilst she crawls to the dry sand above the high tide mark. At this stage of the nesting process female turtles are easily scared away by bright lights and large moving objects. Once she has found a suitable site she uses her front flippers in a swimming motion to scrape a large ‘’body pit’’. She then carefully digs a precisely shaped ‘’egg chamber’’ with her dexterous rear flippers. The dimensions of the nest and the number of eggs laid vary from species to species. On average the nests are about 65 cm deep and the female turtle will lay about 120 eggs per nest. The eggs of most species are about the size and shape of a table-tennis ball. The eggs of the Leatherback turtles are considerably larger. Turtle eggs have a soft shell and are not damaged as they are dropped into the nest. Sometimes, just to be sure, the female will guide the eggs down into the nest with a curved rear flipper.

Once the egg laying is completed, she fills in the egg chamber with sand using her hind flippers. Then she disguises the exact location of the nest by throwing sand behind her using her front flippers whilst gradually moving forward. The whole process (Camouflaging) of nesting can take as long as 3 hours. Finally, the female turtle returns to the ocean. She will be back to the same beach between next 9 and 12 days and nest again. Within a single nesting season, a female turtle can nest up to 12 times (e.g. average -6 for Green turtles in Sri Lanka) depending on the species. When the nesting season is completed she migrates to her foraging ground that may be located thousands of miles away from her nesting ground.

INCUBATION AND HATCHLINGS BEHAVIOUR

Mother turtles do not care for their young like crocodiles and some other reptiles. Instead, once the eggs are laid the female turtle does not have any further contact with the nest and the eggs are left to incubate by the heat of the surrounding sand that is warmed by the sun. After an incubation period of about 60 days the young turtles or ‘’hatchlings’’ begin to break out of their shells and move about in the nest. After a further 2 days most of the eggs will have hatched. The movement of all the hatchlings causes sand from the roof and sides of the nest to fall down to the floor and form a platform. This platform rises as more sand falls and the hatchlings are pushed to the surface with and ‘’elevator-like’’ movement. The hatchlings emerge from the nest at night when it is cooler and they are less conspicuous to predators

This is a particularly dangerous time for the young turtles as there may be many predators such as rats, crabs, dogs and in the morning, birds. Therefore, they immediately and rapidly crawl towards the brightest, lowest horizon, which under natural conditions is the reflection of the moon and stars on the sea. But even those hatchlings that reach the water are not out of danger. The inshore waters are home to many sharks, large fish and seabirds. As soon as they reach the sea, hatchlings swim constantly for about 48hours. During this time they do not feed. Instead they rely on the remains of the egg yolk in their stomachs for nutrition. This is known as the ‘’juvenile frenzy’’ and is an essential behaviour that allows the hatchlings to escape the predator rich inshore waters and be carried away by the open ocean currents. Once they reach these currents, they start feeding on tiny, floating sea animals. Not much is known about their first year, also known as the ‘’lost year’’. It is believed, however, that when the female turtles reach maturity they will return to nest on the same beach where they themselves hatched. It has been estimated that under natural conditions only one in a thousand eggs survive eventually to become mature adult turtles.

MARINE TURTLES FOUND IN SRI LANKA

There are five species of marine turtles found in Sri Lanka.

Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas)

Green turtles have an average length of 1 metre and can weigh up to 230 kg. They are migratory and can be found in all tropical and sub-tropical seas such as the Indian, Atlantic, Caribbean and Pacific Oceans. Green turtles are caught and killed to make ‘’turtle soup’’ which is a delicacy in many parts of the world. Their English name refers to the colour of the fat found under their shells, which is used to make the soup. Young green turtles are mainly carnivorous. The adults however are herbivorous, feeding only on marine vegetation such as sea grass and marine algae. Green turtles are considered as ‘’Endangered’’ species today.

Olive Ridley Turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea)

The Olive Ridley turtle is the smallest of the marine turtles. The adults weigh less than 40 kg and measure up to 65 Cm in length. They are found mostly in the tropical Indian, south Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. They are omnivorous, eating crustacean, fish and some marine vegetation. Olive Ridley turtles are considered as ‘’Endangered’’ species today. Arribada-In a few countries, Olive Ridley turtle nest on a beach in a huge congregation known as an ‘’Arribada’’. This Spanish word means ‘’the arrival’’. For example, in India, 600,000 Olive Ridley turtles have been recorded nesting on the same beach over a period of a few weeks. Despite the apparently large populations Olive Ridley turtles are endangered. This is because so many individuals of this species depend on the security of a small number of important beaches for nesting.

Leatherback Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea)

The Leatherback turtle is the largest of all the marine turtles. They can grow more than 2 metres in length and usually weigh about 600 kg. The largest Leatherback ever found weighed 918 kg! They have a predominant dorsal black colour with variable degrees of white or paler spotting. Spots may be pinkish on the neck. Leatherback feed exclusively on jellyfish and will travel long distances in search of their prey. They have been seen feeding on jellyfish in the waters of Arctic Circle, Leatherback can survive in the extreme cold because, unlike other turtles, they can regulate their own body temperature because layers of fatty tissue insulate their bodies. The English name ‘’Leatherback’’ refers to their unique carapace. Leatherback turtles can dive to depths of 1500 metres in search of deep-sea jellyfish. At these depths the Leatherback’s body is subjected to tremendous water pressure, but its flexible shell does not break and so the turtle can feed safely. Today, Leatherback turtles are considered as ‘’Critically Endangered’’

Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata)

Hawksbills are also relatively small turtles; adults commonly weigh about 60 kg and measure up to 90cm. They inhabit tropical coastal waters around coral reefs and mostly carnivorous. They prey on a large variety of animals including jellyfish, sponges and crustaceans. The Hawksbill turtle gets its English name from its narrow birdlike beak, which it uses to catch animals hiding in small crevices. Hawksbill turtles sometimes eat toxic sponges. Instead of being poisoned, Hawksbills can actually store the toxins in their own flesh. If a human eats the flesh of a Hawksbill turtle he can die from acute food poisoning. The Hawksbill turtle is now highly endangered because for centuries, people around the world have killed them for their shell. Once cleaned and polished, the shell is crafted into ‘’tortoiseshell’’ ornaments. Today, Hawksbill turtles are considered as ‘’Critically Endangered’’

Loggerhead Turtle (Caretta caretta)

Loggerheads grow to 1 metre in length and weigh up to 180 kg. This species nests on tropical beaches and also on beaches in some temperate locations such as the Mediterranean and the South-East coast of the U.S.A. Although this species is one of the commonest species in the world, it is the most rare nesting species in Sri Lanka. From the Indian sub continent, they only nest in Sri Lanka and they show unique colouration suggesting a unique population with unique genes, Therefore, it is very important to take immediate conservation measures to protect the Loggerhead turtles in Sri Lanka. Loggerheads are primarily carnivorous and feed on mollusks and crustaceans. The name ‘’Loggerhead’’ refers to the large head which accommodates a large, muscular set of jaws, ideal for crushing mollusks and crustaceans. Loggerhead turtles are now considered as ‘’Endangered’’

MARINE TURTLES NOT FOUND IN SRI LANKA

Kemp’s Ridley Turtle (Lepidochelys kempii)

Like the Olive Ridley turtles, Kemp’s Ridley turtles nest simultaneously in large numbers. In 60,000 Kemp’s Ridley turtles nested on a beach in the Gulf of Mexico. Today there are less than 2,000 of this species left. They are the most rare species of all the marine turtles. Conservation efforts have allowed the numbers of this species to gradually increase. Nevertheless their precarious situation is a constant reminder of how easy it is to push a fragile marine turtle population close to extinction. Kemp’s Ridley turtles are now considered as ‘’Critically Endangered’’

Flatback Turtle (Natator depressus)

Flatback turtle grow to a length of 100cm and weigh as much as 90 kg. They have dorsally uniform olive-green colouration. They nest only in Australia and although they are fairly common in the Torres Strait and off Queensland, they are regarded as rare because of their limited distribution. Little is known of the diet of the Flatback turtle although seaweed and cuttlefish have been found in their stomachs, Flatback turtles are now considered as ‘’Endangered’’

East Pacific Green or Black Turtle (Chelonia mydas agassizii)

For many years scientists have disagreed about whether the Black turtle was simply a colour Variation of the Green turtle or a separate species. Today the black turtle is recognised by many scientists as a colour variation or a sub species of the green turtle. The Black turtle inhabits the East Pacific Ocean. They are now considered as ‘’Endangered’’

TURTLE NESTING BEACHES IN SRI LANKA

A comprehensive survey of the entire coastline of Sri Lanka for marine turtle rookeries is yet to be done. The map below was prepared from the available nesting data collected by the TCP, NARA and also from observations made by individual researchers.

THREATS TO MARINE TURTLES

Threats for the marine turtles can be discussed under two main categories. They are the natural threats and man made threats.

Natural Threats

The predators represent the main natural threats for marine turtles. Feral dogs. Water monitors, land monitors, jackals, wild boars, mongooses, several

Species of ants and crabs can be considered as natural predators for marine turtle eggs and hatchlings on nesting beaches (Photo no. 31). Killer whales/ Orca whales, Sharks and other reef fishes and sea birds prey on hatchlings in the sea. Sometimes harsh weather conditions such as storms, tornados, draughts and El Nino phenomenon can cause damages to the laid turtle nests.

Man made Threats

Today marine turtles are in great danger mostly due to the activities of human beings, Some of the man made threats are briefly described below.

Kill for meat

Marine turtles are killed for their meat in many countries. In Sri Lanka, slaughter of marine turtles for meat is a traditional practice in many coastal areas. Slaughter of nesting adult females directly effects the reduction of the turtle population. Live turtles entangled in fishing gears are also slaughtered by for flesh by the fishermen.

Kill for shell

The highly endangered Hawksbill turtles have been killed in many parts of the world for its beautiful shell or carapace to provide raw material for the ‘’tortoise shell’’ trade. When scutes are removed from the shell, the turtle eventually dies. Synthetic fibres with similar colour patterns are now available to replace the tortoiseshell dies. Synthetic fibres with similar colour patterns are now available to replace the tortoiseshell raw materials for the good sake of hawksbill turtles.

Egg collection

One of the most widespread forms of marine turtle exploitation is the illegal poaching of turtle eggs . As female turtles come ashore to lay their eggs this makes a easy prey for egg collectors who take the eggs and sell them. All marine turtle nests on Sri Lankan beaches are robbed of their eggs except in places where conservation programmes are implemented. The eggs are either sold at markets for consumption or to turtle hatcheries.

Turtle by-catch

Large number of marine turtles becomes victims of the modern fishing gear. Well over 0000 turtles are entangled annually in floating and bottom set gill nets in Sri Lanka. Shrimp trawling and fishing hooks with baits cause serious damages to marine turtles in other parts of the world.

Non-Scientific turtle hatchery practices

Once in the sea the hatchling swim constantly swim against the direction of the waves for a period of twenty four hours without feeding (Juvenile frenzy), During this period the hatchlings derive their nutrition from an internal, residual yolk, an energy supply that is exhausted at the end of the frenzy. Many hatcheries in Sri Lanka retain hatchling turtles in concrete tanks for at least three days as a practice. When hatchling are kept in tanks for a longer period (e.g. 3-5 Days), the hatchlings spend the first one or two days constantly swimming around the tanks without feeding. On the third day the hatchlings’ behaviour changes to feeding behaviour and because they are kept in tanks with many of their siblings. They begin to bite at each other. Some of the hatchlings receive injuries as a result, which often become infected by bacteria andfungi, thus lowering the hatchlings’ chances of survival.

Habitat Destruction

Important marine turtle habitats such as coral reefs, sea grass beds, mangroves, sand dunes and beach vegetations are been degraded by man in many parts of the world due to over exploitation. Some of the major human activities that cause marine turtle habitat destruction and alteration are briefly described below.

Coral mining

Coral reefs provide an important feeding and relaxing habitat for marine turtle as well as a vital protective barrier for the turtles’ nesting beaches from sea erosion. Sri Lanka’s coral reefs are being destroyed by unsustainable harvesting.

BEACH EROSION

The removal of corals from reefs and sand from the beach increases the rate of beach erosion. The result will be the destruction of nesting habitats of marine turtles.

BEACH FRONT DEVELOPMENT

Large hotels and restaurants adjacent to the beach create a lot of noise and light, This may disturb nesting female turtles. When the hatchlings emerge they can be disorientated by the lights and head for the hotels instead of the sea.

MARINE POLLUTION

Marine pollution claims the lives of many marine turtles, Leatherback turtles feed on jellyfish and they ji mistake plastic bags floating in the water for jellyfish, as the plastic bag block the turtle’s gut the animals starve to death.

In addition, tumor like disease called ‘’Fibropapilloma’’ is a cause for many marine turtle deaths. It is believed that marine pollutants cause this disease. However Fibropapilloma is not seen among the turtle populations in Sri Lanka at the moment.

CONSERVATION OF MARINE TURTLES

Both in-situ and ex-situ conservation programmes are used for the conservation of marine turtles in the world today

EX-SITU CONSERVATION

Ex-situ turtle conservation means the conservation of turtles away from its natural habitat. Ex-situ conservation of sea turtles is conducted by turtle hatcheries. Hatchery owners buy eggs from egg collectors and rebury them in a protected area. There, the eggs incubate and hatch and then baby hatchlings emerge. Then, these hatchlings are collected and kept in tanks for few days and finally released. Badly run hatcheries typically adopt procedures that disregard the sex ratio produced and/or have no regard in ensuring the hatchlings undergo their vital Imprinting. If maintained scientifically, hatcheries can play a key role in marine turtle conservation. In some places marine turtles are raised in farms (for example, Turtle farm in Grand Island) for harvesting purposes.

IN-SITU CONSERVATION

‘’In-situ conservation’’ is the most natural conservation practice among all conservation actions. Conservation of natural habitats of sea turtles allows the turtles to survive under the natural selection. Human impact is kept minimized while the natural conditions are kept maximized. Both nesting female turtles and the hatchling show the highly ecological sensitive behaviours. It is believed that the nesting female turtle’s eventualnest site selection criteria are based on some instinctive factor specifications that only she knows of. In-situ nest protection can be implemented using daily beach patrols and monitoring of nesting activities. In addition, biometric data collection and tagging (marking turtles) could be done to understand the local populations of marine turtles

COMMUNITY BASED EDUCATION AND CONSERVATION EFFORTS

Sea turtles have been used since time immemorial for food and other commodities. Recently, sea turtles have become important for non-consumptive uses such as tourism, educational and scientific research, activities that provide opportunities for employment and information services, as well as other economic gain. Any conservation activities must collaborate with local communities to gain the maximum results and shouldprovide benefits for the local communities. Conduction of public education and awareness programmes can play an important role in marine turtle conservation efforts.